HOPKINSVILLE, Ky. – With the exception of the bailiff, clerk and judge, everyone in Christian Circuit Court Courtroom 2 Wednesday afternoon traveled from either Murray, Paducah or Louisville to attend the summary judgment hearing in a lawsuit between Paducah television station WPSD-TV and Murray State University over public records. The hearing, which most anticipated would take hours and end with a ruling on the case, was over in 15 minutes because a logistics issue prevented the judge from reviewing the exhibits the parties filed with their pleadings.

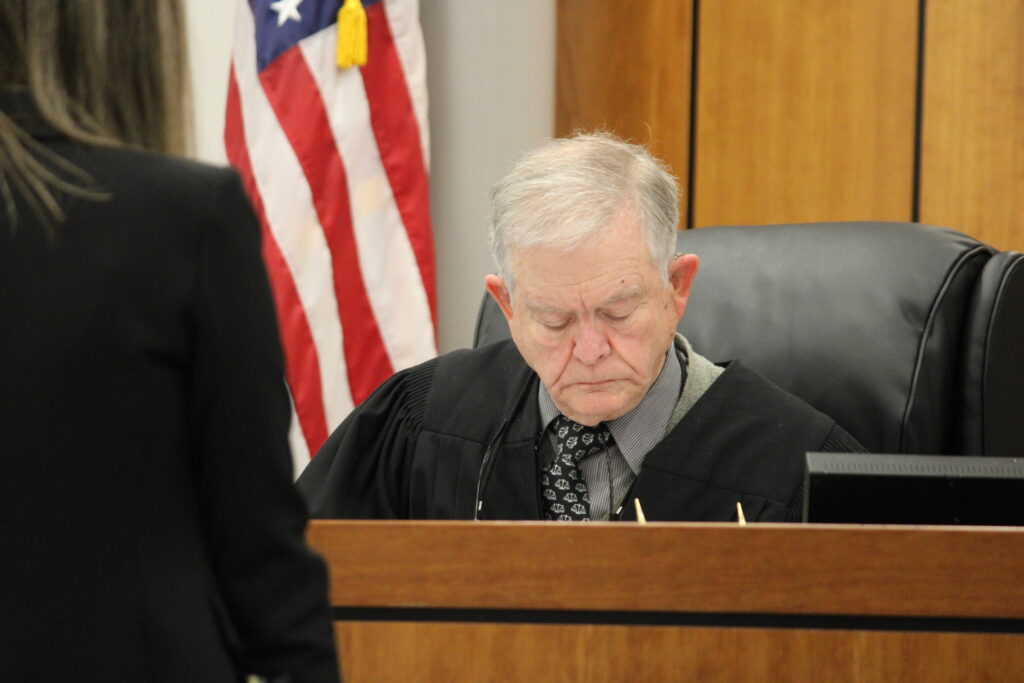

The Calloway Circuit Court case stems from a dispute over information MSU redacted when it produced records in response to two open records requests (ORRs) that WPSD submitted in the fall of 2022. Because a conflict of interest required Calloway Circuit Judge Andrea Moore to recuse, Christian Circuit Judge John Atkins was appointed special judge to preside over the proceedings; however, filings in the case still fall under the purview of the Calloway Circuit Court Clerk’s office, a technicality that became very relevant 11 minutes into the hearing.

“I’m not sure why, but I don’t believe any of your exhibits were accompanying your pleadings,” Atkins said. “I didn’t realize that until yesterday when I was reading back through the file. So, if you would, please supplement the record with any such documentation. I will stand corrected, but when we do these cases by remote control, we can’t just stroll down the hall to the clerk’s office and pick up a copy of some stray pleading that we don’t have a copy of.”

WPSD’s counsel Rick Adams, an attorney with the Louisville firm Kaplan, Johnson, Abate & Bird, asked for clarification regarding whether the exhibits had not been filed or if they had not been forwarded from the clerk’s office in Murray to the judge’s chambers in Hopkinsville.

“I think they must’ve been filed (because) you all refer to them in your pleadings,” Atkins said, “but I just don’t think they made the trip over here.”

Linda Avery served as the Calloway Circuit Court Clerk for 17 years until she retired at the end of last year and was still in office at the time the pleadings Atkins referenced were filed.

“Pursuant to orders of the Kentucky Supreme Court, attorneys have been e-filing in our courts for a while,” Avery said on Thursday. “If memory serves me, April 2023 was the date that the clerks could no longer accept conventionally filed pleadings in cases of this type. Consequently, all pleadings in all cases of this type have been e-filed since that date. While I was clerk, our standard process was to email filings to judicial support staff.”

Avery’s practice of emailing filings instead of mailing hard copies in cases where special judges had been appointed is consistent with the Supreme Court’s long-standing goal to transition from paper files to fully electronic case records.

KYeCourts is the “sweeping, multi-year initiative to update court technology” in an effort to “meet the demands on the court system and enable the courts to stay current with the mainstream of law and commerce,” according to a press release from the Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC).

Updating the court’s technology infrastructure was a key objective for retired Chief Justice John Minton from the time he was sworn-in in 2008, the AOC release states. At the time, Kentucky was still operating a paper court system, putting the commonwealth years behind federal and other state courts in offering e-filing.

Over the course of her tenure as clerk, Avery watched the e-filing system develop. In a Murray Ledger & Times article announcing her retirement, she discussed how the advent of e-filing altered the role of circuit clerks in the filing process.

“Before electronic filing, lawyers used to call me, and I would meet them and take a filing before midnight so it would be current,” Avery said. “With electronic filing, we don’t have to do that anymore. I’ve seen the office evolve from a fully paper office to a hybrid paper/electronic filing, moving toward a complete electronic record.”

E-filing has been available in every county in the commonwealth since 2015. The Supreme Court began ordering mandatory e-filing in specific types of case in July 2022. The court continues to incrementally add to the list of case types that fall under mandatory e-filing. At the present time, e-filing is mandatory for attorneys in 46 different types of cases, and beginning March 1, district, circuit and family court judges will be required to enter orders electronically (e-orders) in those case types as well.

When the statewide roll-out of the e-filing system began in October 2014, 1,800 documents had been filed electronically in the pilot counties. Fast forward to September 2023 when current Chief Justice Lawrence VanMeter noted in his order regarding mandatory e-orders that the system had processed 5.6 million e-filings to date.

“We’re finding that people are filing their cases on weekends and after-hours,” Minton said at an event promoting the statewide roll-out in 2014, according to a McClatchey News Service article. “It makes the court system much more accessible.”

Eight years later, in his final State of the Judiciary address, Minton credited the KYeCourts initiative as the key achievement across his 14 years as chief justice. He noted the system’s growth to include e-warrants and e-EPOs (emergency protective orders) and thanked the General Assembly for authorizing $14.7 million in American Rescue Plan Act funding in 2021, allowing the further expansion of e-filing as well as the creation of a portal for self-represented litigants and payment kiosks, among other things.

“Public institutions face a growing demand for services on digital platforms that are easy to use and easy to access,” Minton said. “Our technology must continue to evolve to meet the changing needs of modern society.”

But the progress made over the last decade was not evident Wednesday afternoon.

Atkins, who was reelected for his fourth eight-year term in 2022, began the hearing by sharing that his typical procedure in summary judgment hearings is to ask the attorneys how they would like to proceed and noted that, most of the time, they choose to rest on their pleadings and let the case stand submitted without engaging in oral arguments.

“This case has been briefed as well as, or better than, most any case I’ve ever had,” Atkins said. “You all have traveled a long way to get here and probably are more interested in having something to say than most of the lawyers are in a situation like this, and I’ll be glad to let you have your say. If you prefer to stand on your pleadings, that’s fine.”

Before hearing from counsel, Atkins asked them to consider limiting the scope of the dispute to one issue to expedite the proceedings.

Adams spoke first and noted that, over the course of the litigation, the dispute has been “whittled down” from thousands to a few dozen redactions. He advised that he was prepared to argue two issues – that the propriety of MSU’s usage of attorney-client privilege and other exemptions should be adjudicated and that MSU’s actions to date constitute a willful violation of the Kentucky Open Records Act.

“Essentially, we’re here 14 months after an open records request was filed, and the law requires records to be produced within five days,” Adams said. “There are things that happened in those 14 months that, we believe, are sanctionable under the statute.”

Atkins told Adams he made a good point but advised his preference is to defer ruling on the willfulness issue until he has been able to examine the unredacted records and MSU’s redaction and privilege logs to ensure all of the redactions were properly made, a process known as an “in camera review.”

“If you don’t think that is crucial,” Atkins said about the necessity of reviewing the records in camera, “and if you bite on what I’m suggesting, then we can decide, really, honestly, to defer ruling on summary judgment to give you all a chance to, in good faith, to try to address the specific matter that I have raised.”

Neither attorney appeared to “bite.”

“To date, unfortunately, WPSD has not explained to us which specific records are at issue,” said MSU’s counsel Alina Klimkina, an attorney with the Louisville firm Dinsmore & Shohl. “If the focus of the issue has really been narrowed to the (attorney-client) privilege documents, we’re talking about 10 documents, which contain some redactions – minor redactions, might I add – which I identified on, of course, Murray State’s privilege log that has been produced as Exhibit 7 to our response. Your Honor, the records which have been redacted based on attorney-client privilege, if that is all that is at issue, we are confident your Honor will find that those documents are privileged.”

Regarding the accusation of willfulness, Klimkina said MSU has “repeatedly undertaken diligent efforts to produce and provide everything that has been requested. What is at issue here is not some smoking gun. Your Honor, we’re talking about very specific, minute redactions, and there’s absolutely no evidence or suggestion, even remotely, of any kind of willful conduct, let alone of bad faith. Sanctions are completely inappropriate.”

Adams agreed that the dispute was over significantly less redactions than it was originally; however, he disagreed that all of the records were properly redacted but added, “We’ll certainly accept the court’s ruling on the privilege issue after the court has viewed the documents.”

“I will say you all have me at a disadvantage,” Atkins said before explaining that he had not been able to review the exhibits filed with WPSD’s motion and MSU’s response and, therefore, had not seen the university’s redaction and privilege logs.

“I apologize that slows you way down, but I wanted to be clear I have not had a chance to review some of the documents that I am confident you believe are of great importance,” he continued. “So, supplement the record with whatever pleadings that you feel need to be placed in the record, (or) it might just be simplest if you just have the clerk send me the court file. I know some clerks don’t like to do that, or I could reach out to the clerk’s office… I’ll just take that on.”

Klimkina offered to leave the hard copies of the exhibits she brought with her, and Atkins accepted. After a brief discussion clarifying the process for the in camera review, the hearing concluded.

“Judge Atkins deferred his decision on the motion for summary judgment (because) he has not had an opportunity to review the underlying records that are at issue in this case,” Adams explained in a post-hearing interview. “So, we left those today, which will help color the arguments that the court has already read. Then after this, we will go back and submit, in camera, every document that has been produced in this case for the court to review and determine which redactions are appropriate.”

When asked about a potential timeframe for the judge to make a ruling, Adams could not speculate.

“He can act as quickly as he wants,” Adams said. “Open records cases should take priority on the docket, but with the logistics of getting documents transferred from Murray to Christian County, it would be hard to speculate.”

Calloway Circuit Court Clerk Melinda Starks said that her office reached out to Atkins’ office on Thursday to find out which exhibits he is missing. As of the close of business on Friday, they had not heard back.

Editor’s note: Stories on this page were written without input or review from our Board of Directors